This Saturday is Dec. 7. Seventy-eight years ago, on Dec. 7, 1941, Japan showed the world what it could do.

Here are seven key takeaways from the U.S.-Japan Pacific War (1941-1945) and from the grand rise & fall of Japan (1868-1945), with an introduction.

The takeaways are my own, and the explanatory text is copied from one of my favorite history books, “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War” (2017) by S.C.M. Paine.

Takeaways, briefly

- The Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942) is why there’s a U.S. military base in downtown Seoul.

- The Battle of Guadalcanal (Aug. 7, 1942-Feb. 9, 1943) is why the Nationalists & Chiang KaiShek survived and why we have Taiwan today.

- The Ichigo Campaign — depleting the Nationalists — is why Mao was able to win and why we have Xi Jinping today.

- Nimitz > MacArthur

- The U.S.‘s 1.) unrestricted submarine warfare (against merchant vessels), and 2.) civilian firebombing together won the war for the U.S.

- Japanese officers who were careful of their men’s lives were considered cowardly, so the profligate were promoted instead.

- Russia, Germany and China are the record-setters for mass murder in the 20th century, but Japan is fourth.

Introduction

Japan and the United States fought their war against each other in a series of peripheral operations; that is, in theaters peripheral to the main theater, which until the very end was China for Japan and always was Japan for the United States. Japanese military planners conceived of Pearl Harbor as one of a series of simultaneous peripheral operations to secure victory in China. The Japanese execution of their war plan was impressive: on 7 December 1941 (Hawaii time), their forces landed in Thailand and half an hour later on the Malay peninsula. An hour later, the Imperial Japanese Navy began the attack on Pearl Harbor. Two hours later the Japanese bombed Singapore. One hour later, the Japanese landed on Guam and began bombing Wake Island. Six hours later they attacked Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Japanese forces also bombed Hong Kong and overran the international settlements in Shanghai and elsewhere in China. Emperor Hirohito’s naval aide, Lieutenant Commander Jo Eiichiro, confided in his diary, “Throughout the day the emperor wore his naval uniform and seemed to be in a splendid mood.”

Operationally, Japan achieved stunning success. The Imperial Japanese Navy took the United States by surprise, sinking four out of eight battleships at anchor in harbor, destroying 180 aircraft and damaging 128 others, much of it parked in close rows on the tarmac. Japan, in contrast, lost just 29 planes and five midget submarines. The Thai government folded within two days. On 15 December the Japanese began bombing Burma. On 16 December Japan occupied the vital Dutch oil field in Borneo. On 25 December Hong Kong fell, followed by Manila on 2-3 January 1942, the Australian military bases at Rabaul on 22-23 January, Malaya on 31 January, Singapore and the Palembang oil fields on Sumatra on 15 February, Lashio on 8 March closing the Burma Road, and Corregidor on 6 May, marking the surrender of U.S. forces in the Philippines. In the first five months of 1942, Japan took more territory over a greater area than any country in history and did not lose a single major ship.

Source: Paine, S.C.M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War”. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Chapter 6 The General Asian War (1941-1945), Subchapter 3 Peripheral Operations, p. 156-157

Takeaways, in full

1. The Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942) is why there’s a U.S. military base in downtown Seoul.

Unknown to the Japanese, the United States had broken their diplomatic and naval codes and so knew the courses of the ships converging on Midway, where it sank four, or one-third of Japan’s twelve, difficult-to-replace aircraft carriers. In doing so, it overturned vague German and Japanese plans to meet up in India and also precluded further Japanese expansion in the Pacific. Midway was Japan’s first major defeat since the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Henceforth it would have to defend what it had. For many months the Imperial Japanese Navy concealed its aircraft carrier losses from both the army and the civilian leadership. It did inform Emperor Hirohito, who had no idea what to do and so apparently kept the bad news to himself. So no one examined how the United States, with inferior naval assets, had miraculously managed to converge them at just the right spot in the vast Pacific theater to sink one Japanese carrier after another. The army continued with its war plans on the assumption that Japan still had twelve carriers.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

2. The Battle of Guadalcanal (Aug. 7, 1942-Feb. 9, 1943) is why the Nationalists & Chiang KaiShek survived and why we have Taiwan today.

Japan’s Southern Advance strategy required a heavily defended outer perimeter of airfields on far-flung islands to parry the expected Allied counterattack. The Imperial Japanese Navy had failed to inform the Imperial Japanese Army that, as attractive as its strategy was, it had not yet built the required Maginot Line of airfields. One of the airfields under construction was at Guadalcanal, which the United States discovered and then attacked on 7 August 1942. The Imperial Japanese Navy desperately called on the Imperial Japanese Army for help. From August 1942 to February 1943, Japan tried in vain to defend Guadalcanal, where U.S. forces pierced the defensive perimeter, halted the advance toward Australia, and forced the Japanese remnants to withdraw. Japan also lost its vital elite cadre of naval aviators, on whom its defense rested. From the second half of 1942 to the first half of 1943, Japanese pilots from land-based aircraft suffered an 87 percent casualty rate and carrier-based aircraft had an astounding 98 percent casualty rate. Although these numbers dropped in the second half of 1943 to 60 and 80 percent respectively, Japan could never replace its lost elite pilots.

Guadalcanal drained so many Japanese resources that, mid-campaign in December 1942, Japan called off the Gogō Campaign aimed at Chongqing. If these losses had not forced deployment of forces from the China theater to the Pacific, Chiang Kai-shek might have lost his last foothold in China to end up at the headwater of the Yangzi river in Tibet or Burma, neither a promising location for a comeback. The Nationalists had fled from Shanghai in 1937 all the way upriver to Chongqing and verged on re-embarking for destinations further west in 1942 until Guadalcanal saved them.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

3. The Ichigo Campaign — depleting the Nationalists — is why Mao was able to win and why we have Xi Jinping today.

The Ichigō Campaign, under the command of General Okamura Yasuji, the instigator of the Three Alls Campaign, was the final and the largest campaign in the history of the Imperial Japanese Army. It ran from mid-April 1944 to early February 1945 and followed the Beijing– Wuhan, Guangdong– Wuhan, and Guangxi– Hunan railway lines. The campaign had multiple objectives: it attempted to carve a passage through central south China to create an inland (and submarine-proof) transportation route between Pusan, Korea and Indochina; to take the airfields in Sichuan and Guangxi to preclude U.S. bombing of Taiwan and Japan; and to target elite Nationalist units to cause the Nationalist government to collapse. Japan deployed twenty divisions composed of 510,000 men against 700,000 Nationalist soldiers. From April to December 1944, the Nationalists lost most of Henan, Hunan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Fujian, and a large part of Guizhou. 25 Key battles included the Battle of Central Henan from April to June, the Battles of Changsha and Hengyang from May through August, and the Battle of Guilin– Liuzhou from September to December. By the time the Nationalists realized that they faced not another Japanese “cut-short” operation, intended to attrite Chinese forces and hold territory temporarily, but the largest Japanese campaign of the war, it was too late. In the first phase of the campaign, lasting until late May 1944, Japan launched a north– south pincer to take Luoyang, Henan and to clear the southern Beijing– Wuhan Railway all the way to Wuhan. Luoyang fell on 25 May. In the second phase, from May to December 1944, Japanese forces cleared the Guangdong– Wuhan Railway, the Guangxi– Hunan Railway, and their junction at Hengyang, the location of the largest airbase in Hunan. On 18 June Changsha finally fell in the Fourth Battle of Changsha, followed on 8 August by Hengyang, on 10 November by both Guilin (the capital of Guangxi) and Liuzhou, and on 24 November by Nanning. In early 1945, Japanese forces broke through to Indochina, opening a continuous land route and eliminating many, but not all, U.S. airbases.

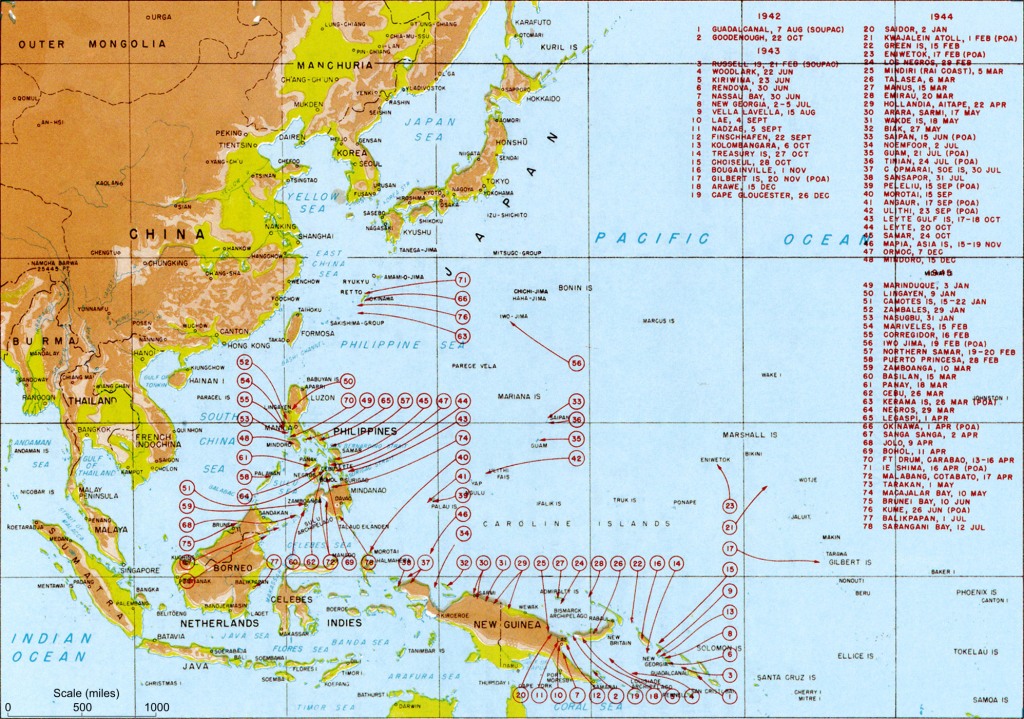

The Nationalists lost over 130,000 killed in action, ten major air bases, and thirty-six airports, as well as their key remaining source for food and recruits with the occupation of Henan, Hunan, and Guangxi. Japanese killed from twenty to forty Chinese soldiers for each one of theirs – a kill ratio attributable to superior conventional equipment. Given the rapid approach of the U.S. Navy to the Japanese home islands – the Marshall Islands in January, the Caroline Islands in February, and the Marianas ongoing – a win in the regional war in China at this late date contributed nothing to the defense of the home islands in the global war.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

4. Nimitz > MacArthur

Meanwhile Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific Campaign, not General Douglas MacArthur’s high-casualty campaign in the direction of the Philippines, delivered airfields in the Marianas, much closer to Japan than the bases in Sichuan. From 16 June 1944 to 9 January 1945, the United States had been able to launch one bombing raid per month from Chengdu with an average of fifty-three planes. Beginning on 24 November 1944, it began bombing raids from the Marianas, running an average of four raids of sixty-eight planes each per month. From March through August 1945, the bombing raids intensified, with daily raids of over 100 planes. As a result, the China theater became irrelevant to the outcome of the U.S. war against Japan. Likewise, Ichigō lost its rationale as the Japanese home islands became the main theater, under air attack not from China, but from the inaccessible Marianas. At the end of 1944, the Japanese called off the Ichigō Campaign in order to redeploy as many troops as possible to defend Japan. Ichigō had a greater impact on the long Chinese Civil War than on the global war by making the Nationalists look militarily incompetent, wiping out Nationalist formations vital to defeat the Communists, and leaving central China wide open to Communist infiltration.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

5. The U.S.‘s 1.) unrestricted submarine warfare (against merchant vessels), and 2.) civilian firebombing together won the war for the U.S.

1.) …the United States used its submarine service to eliminate the Japanese merchant marine, an unexpected primary mission from both the Japanese and the U.S. submariners’ perspective, given the illegality of unrestricted submarine warfare. Pearl Harbor, however, produced an instant change of heart concerning what had been the casus belli of World War I – Germany’s unrestricted submarine campaign sinking the passenger ship Lusitania. The U.S. unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan made German submariners seem like amateurs.

The Imperial Japanese Navy fixated on the heroic task of fighting the U.S. Navy, not picking off sitting-duck merchantmen that posed no match for naval vessels. It fought the symmetric fight, conventional force on conventional force, while the United States also fought the asymmetric fight of naval ship on merchant vessel, imposing unsustainable losses on Japan. Code breaking allowed the United States to predict the location of Japanese supply ships and troop transports, which submarines destroyed with great regularity. During the Pacific Ocean war, U.S. submarines sank 201 warships out of 686 and 1,314 of the 2,117 Japanese merchantmen lost in the war. By war’s end Japan’s merchant marine had been reduced to one-ninth its pre-Pearl Harbor capacity. Only half the men and supplies sent from Japan and Manchuria reached the Pacific theater. The Japanese empire depended on resources and their transport home and its expeditionary forces scattered throughout the Pacific required supplies brought by sea. U.S. submariners starved both the home islands and the expeditionary forces.

2.) … When U.S. precision bombing of Japan proved imprecise and ineffective, the new U.S. commander of the air war over Japan, “bombs-away” General Curtis E. LeMay, who took over on 19 January 1944, realized that Japan’s cities filled with wooden housing and narrow streets made excellent tinder. Despite the shameless false advertising from air-power buffs, precision bombing did not become technologically feasible for nearly three decades until late in the Vietnam War. In the meantime, civilian populations bore the brunt of bombing. The U.S. firebombing of Japan deliberately targeted civilians, who were the overwhelming majority of its victims. It proved brutally successful. During the night of 9– 10 March 1945, firebombing destroyed sixteen square miles of central Tokyo, where the high temperatures made the canals boil. More people died that night – an estimated 84,000 – than were killed during the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Over the following ten days, firebombing destroyed the four next-largest cities: Kobe, Nagoya, Osaka, and Yokohama. By the end of the war sixty-six Japanese cities lay in ruins, leaving 9.2 million homeless. Only Kyoto, Nara, and Kanazawa survived unscathed.

By this time, American military planners understood that Japanese soldiers fought to the death, treated prisoners of war with appalling and also pointless cruelty, and meted out cut-throat treatment to occupied civilian populations. So they focused on minimizing Allied casualties and putting the maximum pressure on Japan in order to end the war as soon as possible. Firebombing met these criteria, but it gave no quarter to the young or old, the innocent or the guilty, the powerful or the powerless.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

6. Japanese officers who were careful of their men’s lives were considered cowardly, so the profligate were promoted instead.

By war’s end, the Japanese had earned a legendary reputation for atrocities. It turns out that they were not particularly good even at taking care of their own. Japanese veterans and witnesses described the common practice of executing their own men who could not keep up and encouraging, if not requiring, Japanese civilians to kill their families and themselves rather than surrender.

The Imperial Japanese Army leadership did not look kindly on those who failed in combat – either enemy prisoners of war or their own soldiers. According to the 1908 Army Criminal Code,

“…A commander who allows his unit to surrender a strategic area to the enemy shall be punishable by death … If a commander is leading troops in combat and they are captured by the enemy, even if the commander has performed his duty to the utmost, he shall be punishable by up to six months confinement….”

It was illegal for Japanese forces to withdraw or surrender. This meant that officers who were careful of their men’s lives were considered cowardly. So the profligate were promoted instead. The 1941 Field Service Code ordered Japanese soldiers, “Do not be taken prisoner alive.” So often they did not take others alive either and their enemies responded in kind. Such rules and the attitudes embedded in them made for a brutal war and a historical legacy that still haunts the Japanese, despite all their numerous achievements in other areas. As the Second Sino-Japanese War protracted and then metastasized into a world war, the Imperial Japanese Army became increasingly brutal with the blockade, massacres, germ warfare, the 1940 Three Alls strategy (kill all, burn all, and pillage all), depopulated zones, death marches, internment camps, and biological experiments on prisoners. When the tables turned, others felt little compunction about raining down firebombs and atomic weapons on them.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

7. Russia, Germany and China are the record-setters for mass murder in the 20th century, but Japan is fourth.

Japan’s brutality proved singularly counterproductive. If the goal was empire and autarky, making the colonies ungovernable by leaving the colonial population no alternative but resistance indicated a stunning lack of perception. Everywhere the Japanese went, they alienated those whom they encountered. They conducted serial disingenuous diplomacy with the United States, Germany, China, and Russia, alienating each in turn. Despite great expertise in the technical aspects of economic development demonstrated in Manchukuo, Japan’s gratuitous brutality transformed potential sympathizers into bitter enemies, particularly in China, where their cruelty transformed a fractured people into a deadly foe, and also in Korea. For a short time Asians living in the Pacific theater looked upon Japan as their liberator from the colonial powers, but Japanese actions rapidly made clear their own colonial ambitions. Their oppressive rule soon outdid all powers save Russia, Germany, and China, the record-setters for mass murders in the twentieth century.

Japan’s quest for national security via war destroyed 66 percent of its national wealth, 25 percent of its fixed assets, 25 percent of its building stock, 34 percent of its industrial machinery, 82 percent of its merchant marine, 21 percent of its household property, 11 percent of its energy infrastructure, and 24 percent of its production. Between 3 and 3.5 percent of Japan’s population died in the Pacific War, which, including all sides, took 20 million lives. From 1937 to 1945, 410,000 Japanese soldiers died in China – 230,000 after December 1941. Nine hundred thousand were wounded. They killed at least 10 million Chinese soldiers and civilians – a conservative estimate. Some triple this number. Whatever the toll, China suffered far more casualties than any other part of the Pacific theater of World War II where Japan’s military operations threatened or occupied lands with nearly twice the population of those so abused by Germany.

The costs for Japan did not end with the war. Russia took 639,635 Japanese prisoners, including 148 generals, and kept most of them for four years of forced labor in violation of Article 9 of the Potsdam Declaration. The last prisoners did not return home until the 1990s and 62,068 died in captivity. Although Japan released thousands of Western prisoners held in its internment camps, which were known for their brutality and high mortality rates, it held virtually no Chinese prisoners of war. Apparently, those captured alive and not summarily executed became forced laborers often sent to Manchukuo. Despite fifteen years of war in China, the Japanese allegedly held only fifty-six Chinese prisoners of war at the end of World War II – a death rate outdoing even the extermination camps of the Germans, a hard record to beat. Apparently, the Chinese did not take prisoners of war either.

Source: Paine, S. C. M.. “The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War.” Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Categories: Uncategorized

Leave a comment