Do you live in Seoul? Do you think a lot about your city?

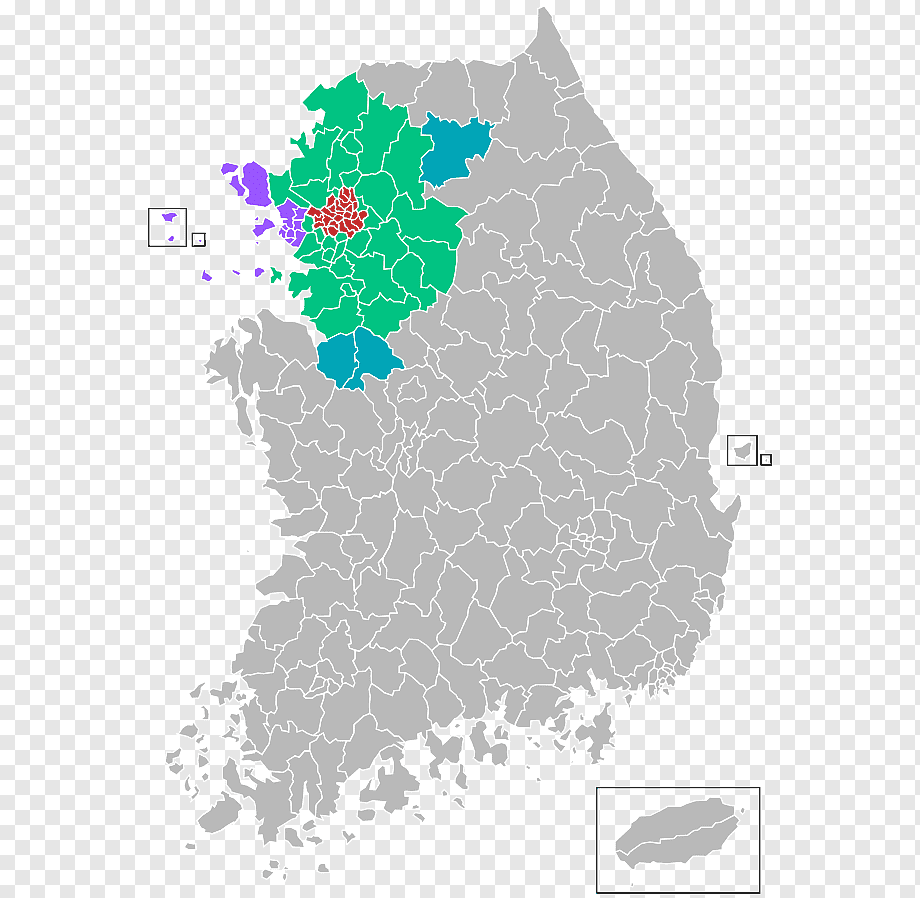

The greater Seoul area has about 26 million people in it. It’s about 50% of Korean GDP and about 50% of the population. Seoul proper, just the 25 boroughs, at the heart of the greater Seoul area, has just under 10 million people.

Seoul is a city of two faces. Major central planning efforts have made Korea’s capital one of the safest, cleanest, and most public-transit oriented cities in the world. Yet its labyrinthian network of streets, restaurants hidden in dark alleyways, and entire buildings filled with a medley of shops reveal another side of the city that is more spontaneous and idiosyncratic.

This paradox between centrally planned and chaotic Seoul is one that is tackled every day here. Inspired by the science of complex systems, I want to demonstrate how Seoul is shaped not solely by disorder or grand design, but also by the intermingling of daily small choices that create spontaneous patterns from the bottom up. I might even give you a few tips on how to consciously harness them. Just as everyone in New Yorke’s Upper West Side only lives in their neighborhood, so, too, do Seoulites only live in their neighborhood.

Seoul is “emergent” urbanism. What is emergent urbanism? (Basically, big.) How can it demystify Seoul? (Walk around it.) What are the lessons cities around the world can take from Seoul’s example? (Well, there are a lot.)

The general definition of “emergence” is the creation of order and functionality from the bottom up. So certain orders or functionalities can happen without the need for a central brain that organizes everything. It’s based on the idea that systems and phenomena, through local interactions of their parts, can create order. The classic example would be the flocking behavior of birds, in which you can see clearly the formations, but there is no sole bird leading it.

The simplistic discourse, until now, has described Seoul as a city of chaos. I am against that. It’s a bit of an Orientalist trope that we apply only to massive East Asian cities where we can’t read the local alphabet. For me, in Seoul, I want to emphasize the order that can be found across my city, but without denying that it’s a very different kind of order from the one we see in small cities like London, Paris, Berlin, or Barcelona, which all have much stronger top-down urban planning.

Seoul is “emergent” in that it has complex adaptive systems. I find these configurations in many Seoul neighborhoods. They are accelerators of interactions and, therefore, of adaptations.

Most people who live in cities will have a sense of what I mean. You see it in every massive city around the world: these large-scale, usually high-end developments, that shape a whole district according to a grand corporate plan. However, when you walk through them, you don’t really feel like you’re in a particular place. You’re in this generic place that’s everywhere and nowhere at the same time. You’re in an airport, basically.

There is economic logic to these developments. If you’re developing something on a large scale, you want to get a high return. So you’re usually looking at luxury condos stacked over high-end retail and restaurants, maybe with some anchoring project, like an art gallery, and also what’s called “POPS,” or, privately owned public space. Have you seen the new developments at Seoul Forest? Look at Galleria Forêt (한화갤러리아 포레) or at Acro Seoul Forest (아크로 서울포레스트디타워), or even at Trimage (서울숲 트리마제 688세대). Elsewhere in Seoul, you can look at the development around Yongsan Station/ Dragon Hill Station (용산역). In both boroughs, all those developments are luxury condos stacked over high-end retail.

There are rational reasons to have such projects, but there are things that such corporate urbanism can’t easily bring to Seoul, like a sense of community, spontaneity, idiosyncrasy, or surprise. This is the humanity that really makes Seoul a flourishing and exciting place to be. We only live in our neighborhoods.

There are a number of reasons why small businesses in Seoul are so vibrant. First, look at cities around the world. How many flexible microspaces are available? By microspaces, I mean small little nooks and crannies in the commercial or residential sectors of the city where you can do a lot of different things, and don’t need to pay a huge amount of money in rent.

This is going to sound wild to anyone who lives in Canada or the U.S., but for any two- or three-story jutaek (주택) in Seoul, the owner can by right operate a bar, a restaurant, a boutique, or a small workshop on the ground floor, even in the most residentially-zoned sections of the city. That means you have an incredible supply of potential microspaces. This is particularly visible in the neighborhoods of Thick Rock (후암동, 厚岩洞), Freedom Village (해방촌, 解放村), and Next Writing (문래동, 文來洞). Any elderly homeowner can decide to rent out the bottom floor of their place to some young kid who wants to start a coffee shop, for example. When you look at what we call golmok alleyways (골목) — charming, dingy alleyways that grew out of the black markets, out of post-Korean War Korea, which are some of the most iconic and beloved sections of the city nowadays — it’s all of these tiny little bars and restaurants just crammed into every available space.

Of course, regulation at all different levels figures into this. It’s an incredibly dry topic, but actually the way in which you regulate small businesses and spaces changes everything about the emotional color palette of your city. In Seoul, for example, small businesses get a lot of interesting tax incentives. Liquor licenses are extremely cheap and easy. (A liquor license in a U.S. city can sometimes run up to $500,000, so you’re not going to have a little four-seat, mom-and-pop bar there for the locals.) The regulatory and policy choices we make fundamentally determine what our cities are going to ~feel~ like.

When you look at the most charming and historically interesting neighborhoods and districts of Seoul, they have faced a lot of different threats over the years. Any of these districts that haven’t fallen to fires, mudslides, or to property redevelopment usually have some resilient plan in place for how they don’t just get turned into luxury condos or Starbucks. Sometimes they put all their land into a nonprofit trust and only rent it out to folks who are going to continue the sort of business the neighborhood is famous for. Sometimes they lobby to get themselves declared a “culturally significant” area so that developers are less likely to swoop in. Sometimes they upgrade as best they can without needing to completely redevelop the area and lose its charm. A lot of these neighborhoods have over time been redeveloped. There are many more specialized “food alleys” in Seoul neighborhoods nowadays, evidence of such efforts. Keeping the old, developing into the future.

I’d also say that there are a lot of different places to build in Seoul. The subway network is vast and ubiquitous. If you’re a corporate developer looking to build something new, you could spend decades trying to get neighborhood people with weird labyrinthine property rights to agree… or you can just find a less-developed place in the outer districts of the greater capital area where there’s an old government building or something. At this point, in post-COVID 2024, there are easier methods than trying to force out the classic districts with their long-term tenants.

Traditionally, I would say that people in Seoul are quite invested in their communities and probably consider the neighborhood as a whole much more than they used to. There is a culture in which Seoulites are invited by the environment or institutions, like neighborhood associations, to think beyond their narrow interests. This is, in fact, strengthening, with many new libraries and community centers being funded at the –gu/ borough level. (There are 25 boroughs in Seoul.) Interviews with the various –gu/ borough mayors reveal much about the city. Many of those interviews can be found in English at either Korea.net or at the Korea Times: neighborhood mayors working on redeveloping their boroughs.

More generally speaking, in the U.S., debates about urban policy are skewed by the fact that a homeowner’s property (primary residence) is normally their single largest asset, the closest thing they have to a savings account. Usually for retirement, people are counting on their property values to go up, so they have a strong incentive to resist change that might threaten that. A lot of the dynamism we see in the “emergent” urbanism of Seoul, however, are things that reduce predictability, i.e., new construction, which could possibly reduce property values. Experiment, see what works, reward the victorious.

Not everything can or should be designed “emergently,” however. Obvious examples would be subway/ train infrastructure or disaster preparation. (The Han River floods, at least partially, most summers.) Parks and green spaces are another, especially big parks. Many things need to be centrally designed and planned, not only in terms of architecture, but in terms of society as a whole.

One of the drawbacks in Seoul is that “emergent” functionality was a bit unconscious until now. There were certain conditions that happened and it worked very well. However, when the conditions change, people need to be aware. They need to be more active to keep the “emergent” functionality. People create collective properties to be more resilient against redevelopment. This is what is happening in many golmok alleyways; the most famous failure of this would be the Avoid the Cops Alleyway (technically, Avoid the Cavalry Alleyway) (피맛골, 避馬街) in Central Borough. (This was a parallel back alley to the main street, down which commoners could walk without having to encounter a royal carriage. In modern times, it became a good restaurant/ drinking/ night spot. Then there was a fire, and then it was redeveloped. Today, it’s chain restaurants on the lower levels, and offices at the higher levels.) Golmok alleyways without collective property are in a very weak position. I think that that vulnerability has increased because of corporate redevelopment. So if people want to keep things in this “emergent” condition, there is a need to be more aware and active. You cannot leave it to chance. You need to be more conscious, mobilize and organized.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-IOTR53ga8M

Anyway, at least Seoul is lucky in that it’s not swamped with tourists, like Bangkok or Barcelona. Seoul really is for the Koreans, the Seoulites, the locals, and that’s part of why I love to live here.

–inspired by & partially stolen from Max Zimmerman’s article “Why Neighborhoods and Small Businesses Thrive in Tokyo,” July 22, 2022.

All photos stolen off the internet.

Neighborhood name translations are my own. Please correct me if you feel there’s a more appropriate nuance. I miss a lot when dealing with Chinese characters.

Categories: Uncategorized

The direct translations were cool 😉

And nice Matteo Ricci logo ~

LikeLike